One Attacker's Trash is Another Attacker's Treasure: A New Ecosystem Drives Cybercrime Innovation

Raveed Laeb, Product Manager

BOTTOM LINE UP FRONT

The cybercrime financial ecosystem constantly adapts to meet innovative, emerging business needs. Buyers are interested in gaining the most data in the easiest, most frictionless way possible – and threat actors are glad to lend a helping hand: from Malware-as-a-Service, to monthly subscriptions and data breaches, new services are popping up on a daily basis.

This entry focuses on one interesting trend taking hold in many communities: the direct and targeted selling of data obtained from banking Trojans and infostealers. This is carried out both directly by threat actors in cybercrime communities and throughout specialized automated markets, and emphasizes a threat against enterprises: actors monetizing corporate credentials. However, these robust and vibrant markets also provide a great theatre for intelligence collection and an opportunity for defenders to have a look directly into cybercriminals’ operations.

MALWARE-AS-A-SERVICE… AS-A-SERVICE

Cyber criminals make money out of your personal login data. Nothing new so far, right? Monetizing compromised banking credentials through money laundering schemes is the prevalent business model behind the appropriately named banking Trojan industry. Infect a wide variety of victims, siphon as many credentials as you can, and voila – you’ve got a hotbed for financial crime and fraud.

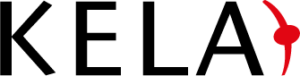

The process, however, may not be as straight-forward as it sounds; maintaining a widespread banking botnet operation involves loads of hard work. Schematically, we can describe the main stages in the process as such:

The past two years have seen a distinct servitization trend in both coding and spreading a malware, mostly via the variety of malware-as-a-service providers operating within the cybercrime financial ecosystem; and while every stage above deserves a whole series of articles, this particular entry will focus on the last stage – monetization.

Monetization is an interesting phase to look at since, as opposed to earlier phases where group members communicate internally in secure back channels, it forces different threat actors and groups to communicate with each other – often using different forums, e-commerce platforms and online markets. These communications provide crucial intelligence-gathering opportunities.

UNKNOWN UNKNOWNS

The cybercrime financial ecosystem is sprawling with sellers of stolen credentials. From illicit markets, through the so-called “auto-shops”, and to the traditional cybercrime forums – you can find peddlers of compromised login data within every corner of the cybercrime financial ecosystem.

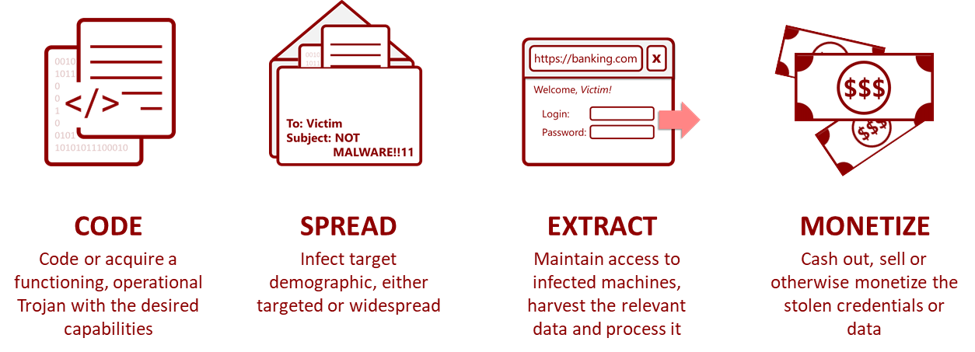

Below is a standard forum listing. In it, we can see a threat actor offering Canadian banking credentials for sale on a major carding and fraud forum.

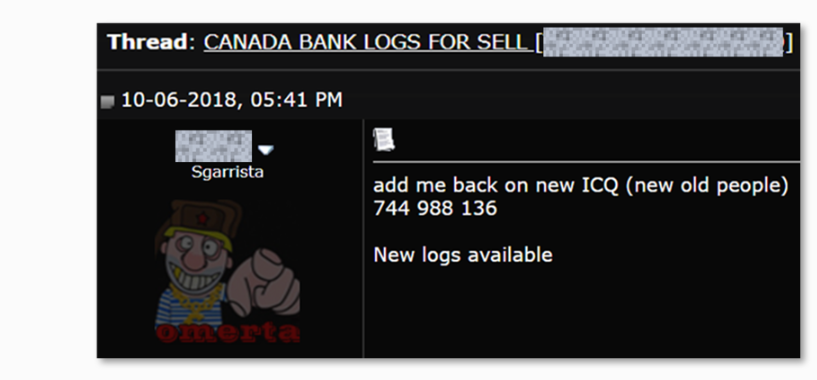

What we can assume happened here is that the actor went through his thousands of unique stolen logins and looked for ones that would attract buyers; in the cybercrime financial ecosystem, these would most probably be retail, e-commerce and banking credentials. This has a major pitfall though – threat actors face unknown unknowns that may be damaging their profits. One attacker’s trash can be another attacker’s treasure, and peddlers of compromised credentials are in a constant race to understand how to separate trash from treasure and price them accordingly.

The filtering process threat actors go through before selling credentials in the old school way – identify the assets that are worth a lot of money and isolate them, sell them for a proper price, and then sell all the other credentials in bulk. The million-dollar question is: Which account goes into the trash bucket, and which is a potential treasure?

Sellers tend to target the “low-hanging fruit” – the product most fraud actors would like to buy since they’re relatively simple to “cash out”, hence the usual focus on banking and e-commerce. This may create an absurd situation in which a compromised machine hosts credentials for, say, a sensitive government service that may be worth thousands of dollars for the right buyer – but the actual data is offered for sale for a few dozen bucks based on the fact that the machine also had an available login for a retail banking service.

Let’s take the Target breach as an example: it’s safe to assume that fraud-motivated threat actors would pay more attention to easily monetized banking or retail credentials circulating in forums, while disregarding the Target extranet Fazio Mechanics logins. But as the breach teaches us, esoteric credentials can be of high worth to the right buyer, just as the compromised Fazio Mechanical credentials presented by supplying attackers with the initial foothold into Target’s network.

These unknown unknowns – the possible gems hiding in the data, which may not be obvious to the seller but may be worth a lot of money to the right buyer – are becoming increasingly more significant as markets grow and cybercrime TTPs and monetization channels adapt. Specifically, we note a growing interest of threat actors searching for the less popular items, such as ones that require a more complex cash out method.

Threat actors in a closed Russian cybercrime community: “working with US links (not banks) [United States-based stolen credentials – KELA], need partners who have a lot of live bots or fresh logs from this country”; the threat actor is interested in specific credentials not belonging to banks, i.e. ones that wouldn’t have been identified by the botnet operators themselves as interesting.

SHIFTING BUSINESS MODELS

Threat actors are shifting towards a more customized monetization method for stolen credentials, based on a growing interest of buyers in more targeted and esoteric credentials. With a previous focus on the “low hanging fruits” method as described above, threat actors now put emphasis on providing buyers visibility into the guts of the campaign – allowing their buyers to interact with the data hands-on.

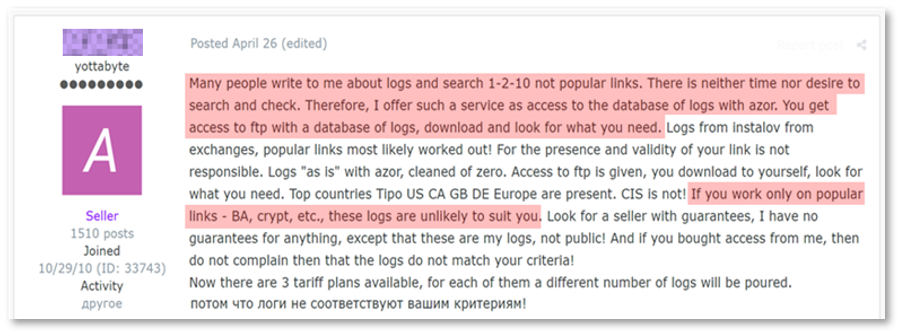

An interesting example is a threat actor operating in a top-tier Russian forum, who describes the pains that come with the filtering process:

Straight from the horse’s mouth – a cybercriminal explains the pain business in the credential stealing business model

In order to accommodate buyers’ needs, the threat actor skips the processing phase and instead uploads all compromised data to an FTP server from which buyers can get access to the full datasets and harvest the credentials that interest them. This business model works as a service – buyers pay the actor a monthly premium fee and in return gain access to an updating dataset maintained by the actor.

This service, however, can be a bit pricy for buyers, reaching thousands of USD to maintain yearly access. Here pay-per-bot markets come into play. Unlike the service model above, these botnet markets – with the infamous Genesis Store being the pioneer and business role model – allow buyers to view basic data belonging to an infected machine, without seeing the full credentials. A buyer can search for machines supplying the credentials of interest, but must complete full payment prior to accessing the desired credentials. This model eases the pain points cybercrime “business owners” are suffering from in terms of unknown unknowns: instead of selling singled-out credentials from a pre-determined list of easily monetized services, they can flaunt their full inventory for potential buyers.

Sensitive organizational credentials offered for sale on two different bot markets

The cyber security media tends to refer to these types of markets as an interesting venture in cybercrime mostly due to the fingerprinting abilities. However, our view of these markets as an interesting source relies on the mere visibility into how the campaign is spread. With a trend of botnet operations shifting towards targeting corporate resources rather than consumer targets, this visibility into real, live infections can be crucial in identifying threat actors’ access to sensitive corporate credentials.

THE CASE FOR AN ENTERPRISE DEFENDER

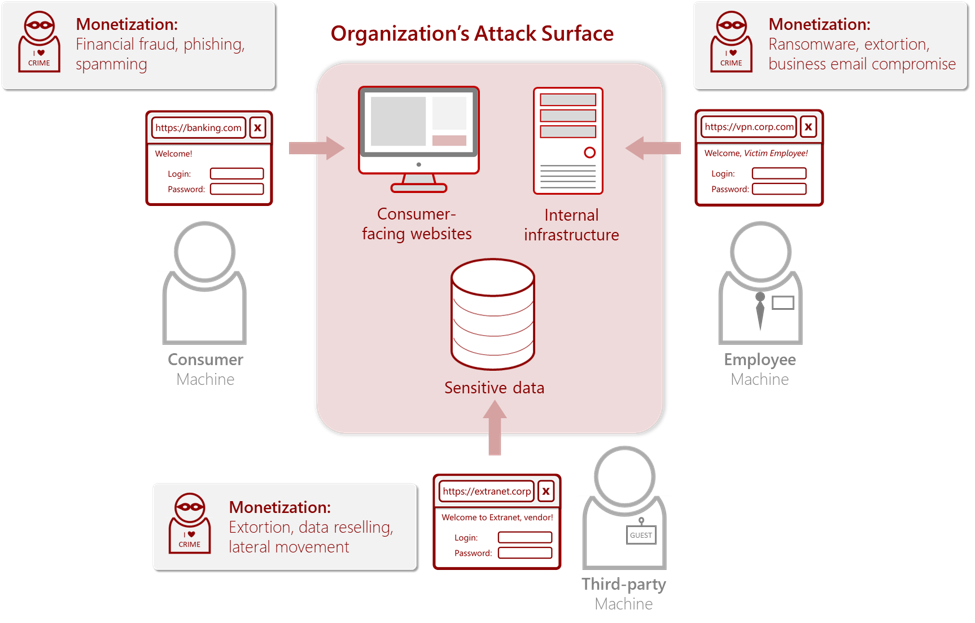

The operators of said botnet markets are all but targeted, and seem to have one central goal: infect as many machines as possible, regardless of the type of credentials they harvest. This creates a varied inventory for botnet markets – a plethora of compromised machines from different geographies that host credentials for anything from banking services or social media to sensitive internet-facing assets belonging to government agencies. This highlights the dual nature of these markets: an organization can be exposed both from its consumer-facing assets, as well as its employee-only assets. To simplify this concept, think about the difference of data that would be obtained from an attacker targeting your personal, home-used machine vs. your business workstation machine; the first might yield social media and banking credentials, while the second may have corporate email, task management or sensitive cloud platforms credentials.

The dual nature of account compromise and use cases. An organization’s attack surface is comprised not only of network infrastructure but also the humans that access it – be it employees and vendors that access assets directly or consumers that access the business’ services or products. Each has its own usage for cybercriminals.

As botnet markets offer their users intuitive user interfaces and advanced search capabilities, they also give a possible attacker an inherent edge: a highly increased visibility into the arsenal of compromised credentials. Thus, monitoring the right assets is crucial for defenders; a fraud team’s interest might be in the business’ consumer-facing web applications, while threat intelligence personnel would want to monitor crucial internal applications, third-party access to business resources or network gateways.

In over a year of monitoring these types of markets, KELA was able to trace numerous corporate credentials and pass them on for remediation – including credentials for corporate VPNs, development environments, employee webmail clients, and more. These serve as easy-to-grasp examples on how classic threat models can be monitored in these markets.

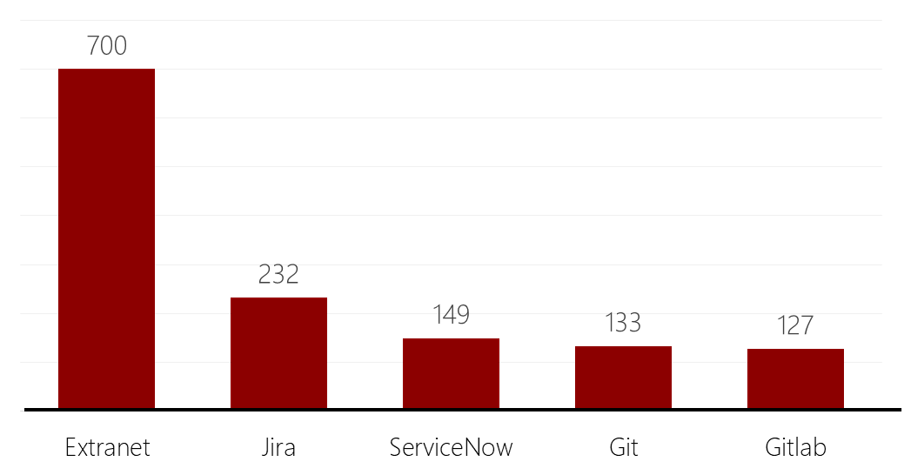

Looking at the numbers can quickly show how the market is such a huge trove of sensitive data for any interested attacker. KELA analyzed data from the Genesis Store, looking for sensitive services that may be utilized by threat actors for further exploitation, ransom or lateral movement – and found thousands of sensitive corporate credentials available for purchase.

Number of unique instances of sensitive corporate services that have exposed credentials on the Genesis Store

These sensitive credentials aren’t directly offered as monetized access to corporate assets – instead, they’re waiting in a trove of data comprised of hundreds of thousands of credentials. In the olden days of selling only easily monetized credentials on forums, the credentials in the graph would probably not even go through the filtering stage and would end up in the trash bucket. However, new business models that allow for better utilization of stolen data make these sensitive credentials readily available for any actor with the right connections. In these scopes and numbers, defense becomes a number-game: have as many eyes in the right places and perhaps you’ll catch your Jira credentials as they’re offered for sale.

A LESSON LEARNED

A January 2017 paper examining the Target breach noted: “It is not known if Fazio Mechanical Services was targeted, or if it was part of a larger phishing attack to which it just happened to fall victim.” Truth is that it doesn’t matter if any organization is directly targeted or just falls prey to a wider campaign; as long as threat actors have access to compromised credentials that belong directly to your organization, your employees, or your third parties, you may be at risk.

This is where external threat intelligence comes into play: the ever-changing business models and monetization channels employed by threat actors, as can be seen in the cybercrime financial ecosystem (read: “Dark Net”), are amazing intelligence-gathering opportunities. Peeking into actors’ monetization processes, where inter-group communication occurs, enables organizations to detect when their organization is being spoken about by attackers. The previous outlook of targeting the “low-hanging fruit” has taken a new form, with prior overlooked information – or unknown unknowns — proving a great significance in the cybercrime financial ecosystem. Nowadays any small piece of information can be of strong importance to different members among the cybercrime financial ecosystem communities. While there is no silver bullet or one-stop-shop for cyber security, implementing the proper intelligence tools can give you a look into what attackers are discussing, with the goal of preventing an attack before it happens.

Are you an enterprise defender interested in enhancing your visibility into the cybercrime financial ecosystem? From corporate credentials traded in botnet markets, through attack surface mapping to fraud and phishing schemes – KELA’s RADARK provides an unparalleled visibility into the inner workings of the Dark Net. Reach out, schedule a demo and learn how threat actors are seeing you!